Hiking in the Sierra Nevada, arguably the West’s greatest mountain range, is a California birthright. It’s also the birthright of every American. When you walk along the crest of these majestic mountains, you likely are traveling on the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,650-mile path for hikers and horseback riders that provides access to acres of public land in California, Oregon and Washington.

In 1968, a bipartisan Congress passed the National Trails System Act, creating the National Trails System and designating the Pacific Crest and Appalachian trails as the first two national scenic trails. Four years earlier, the Wilderness Act sought to preserve the country’s best landscapes from mechanization and development. Today there are 11 national scenic trails, 19 national historic trails and 109 million acres of protected wilderness.

There is pressure on public lands from development, energy extraction and climate change. H.R 1349 is simply another attack, a Trojan horse couched in false claims of denied access for bicycles.

This is our American legacy.

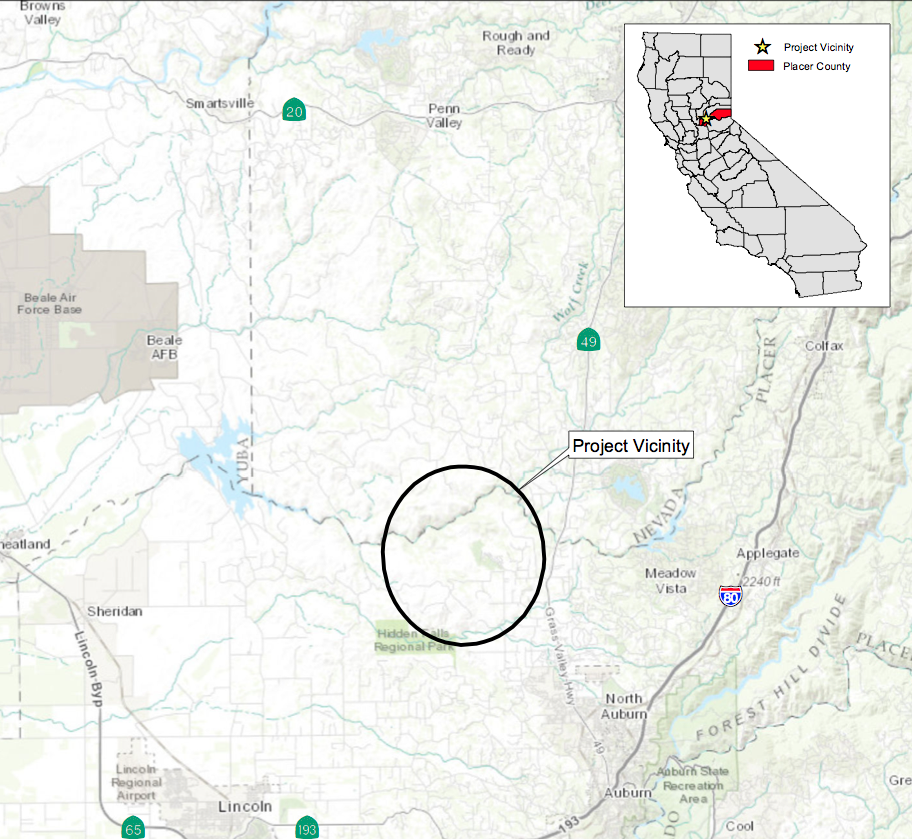

There is a looming threat to these protections. A fringe group of mountain bikers selfishly hopes to renegotiate the high standard enshrined in the Wilderness Act. H.R. 1349, a bill by Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Elk Grove, seeks to open wilderness trails to mechanized travel under the guise of fair access to public lands.

The so-called “Wheels over Wilderness” bill would undermine the character of wilderness as it’s so clearly defined by Congress. The act states: “...there shall be no temporary road, no use of motor vehicles, motorized equipment or motorboats, no landing of aircraft, no other form of mechanical transport...”

This is part of a larger scheme. Some in Congress are doing all they can to undermine protections for our public lands and the agencies charged with managing them. And the Trump administration has curtailed the boundaries of two national monuments and proposed massive cuts to federal budgets for maintaining trails.

There is pressure on public lands from development, energy extraction and climate change. H.R 1349 is simply another attack, a Trojan horse couched in false claims of denied access for bicycles. But cycling is well accommodated on public lands. The U.S. Forest Service says that 98 percent of its non-wilderness trails are open to bicycles.

The Pacific Crest Trail Association and others, Including the International Mountain Bicycling Association, oppose this bill because we value the wilderness as it is. Half of the PCT is wilderness, so there is much at stake for the trail and the 48 wilderness areas it crosses. Only three percent of federal land in the lower 48 states is protected wilderness. The rest is open in a variety of ways to all forms of recreation.

The PCT was built by and for people on horseback as well as hikers. A fast, silent bike can easily spook a horse that might see it as a predator. What would happen on a narrow trail with steep drop-offs?

We are not against mountain biking. We think the PCT and wilderness should remain free of bikes because that’s exactly what Congress intended. We are committed to working with cyclists to ensure their needs are met. But H.R. 1349 drives a wedge between groups that should be partnering to protect public lands. It would give hundreds of local land managers discretion over how wilderness trails are used. Cue the conflict.

It is becoming more difficult to escape technology and crowded cities. Wilderness, which provides clean air and water and allows wildlife to thrive, must be saved for future generations.

Any erosion of these protections would be a mistake. Opening the door on debate may be opening a Pandora’s box on the idea of wilderness itself.

--

Liz Bergeron is executive director and CEO of the Pacific Crest Trail Association.

Reach her at [email protected].

CLICK HERE to see the original article in the Sacramento Bee newspaper.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed