If the project’s details are approved, the Federal Emergency Management Agency will cover 75% of the $6 million total cost, Tarr said.

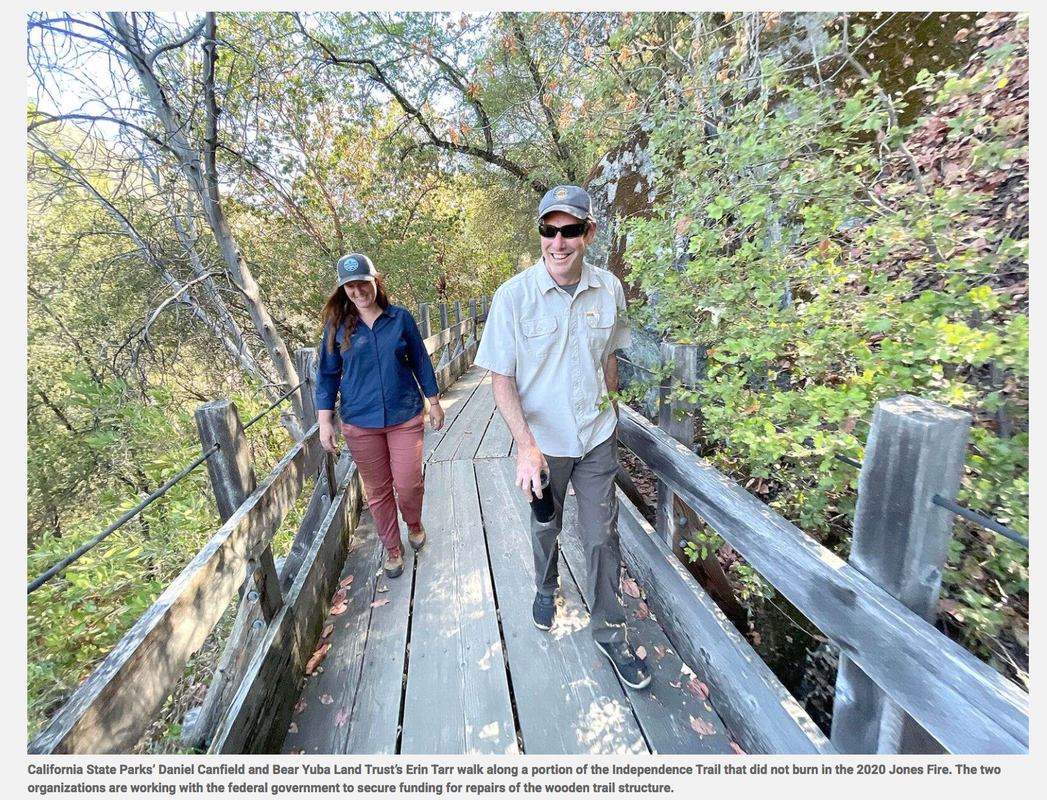

According to Dan Canfield, the Sierra District superintendent in the State Parks Department, the entire sum required from the federal government will ultimately go to two different entities — State Parks and the Bear Yuba Land Trust. “The Independence Trail, as it runs along the river here, crosses different land ownership,” Canfield explained. “The federal government treats it differently depending on whose land it’s on.” Because one owner is a public agency and the other private, FEMA treats their applications differently, Canfield said. “We’re in one process on the state side for the damages to state parks, and our neighbors are in another,” Canfield asked.

Tarr said that neighbor is the land trust, which inherited seven interspersed parcels in the South Yuba Canyon in 2012, after the previous owner, John Olmsted, died. Tarr said Olmsted bequeathed the 207-acre parcel — the Sequoya Challenge Preserve — to the trust with the intent that the state would eventually take it over.

When the Jones Fire began Aug. 17, 2020, and burned 705 acres over the course of 11 days, flames indiscriminately incinerated flora and fauna on parkland and the preserve. It burned 40 acres on the Sequoya Challenge Preserve (BYLT land) and about 150 acres on State Parks property.

There were six flumes, one wheelchair ramp to Rush Creek, and an overlook platform destroyed. Four of the flumes and the wheelchair ramp were on BYLT property. “The fire was all on the west side of the 49,” Canfield explained. “It was lightning — caused with the ignition point very close to the confluence of Rush Creek and the Yuba River. Surprisingly, it did not burn the footbridge, but it then burned up to the canyon.”

Tarr said even though the majority of the structures destroyed during the Jones Fire belonged to the trust, the request for federal support was denied because private nonprofits are ineligible for FEMA funding on behalf of “recreation features.” BYLT submitted an appeal to FEMA in June to deem the organization eligible for funding. “That’s kind of the big challenge for me and Erin, to work through and bring the rest of the bureaucracy along with us,” Canfield said.

Tarr said she and Canfield have been working closely with the California Office of Emergency Services, an agency she trusts to see the work to be done as one project. Canfield said it’s “incumbent upon the state” to recognize and distribute the money required, so that the two landowning entities can work together on one unified project. “If we’re going to be successful, we have to work together,” Canfield said. “Who wants a bridge to nowhere, a half a trail?”

Canfield said FEMA ought to offer support to the trust not only to ensure the entire rehabilitation of the trail as opposed to partial rehabilitation, but also because “the trust has a longstanding desire to transfer the property and the trail to the state.” Part of the nonprofit’s appeal included the fact that the Independence Trail was the first handicapped accessible trail in the United States.

“When it was first created in the 1980s, people traveled from Japan to hike on this trail,” Tarr said.

An integral part of the trail’s accessibility were its flumes — wooden structures first employed by settlers to convey gold and water across ravines along steep mountain slopes, Canfield said.

According to Canfield, the flumes located on the Independence Trail were made in the 1980s and therefore not considered historical. The Excelsior Ditch, which runs alongside and even becomes the trail on the east side of Highway 49, is.

“Whenever the Excelsior Ditch encountered a canyon, the pioneers would build these wooden flumes, which are wood boxes to convey water so the ditch could continue to run alongside the cliff,“ Canfield said. ”The flumes that got burned up by the fire aren’t that old, but they are an important trail feature that accommodate lots of different types of hikers. The flumes were not historic, but the ditch is.“

When Olmsted rediscovered the rock-lined ditch in 1969, he thought the former water conveyor seemed wide enough for wheelchair use, Tarr said. “His step daughter was in a wheelchair and she just said she wanted to go out in the wilderness and touch nature,” Tarr said.

Tarr said John Olmsted’s son, Aldon Olmsted, created a film to help raise the remaining $1.5 million FEMA will not cover to complete the project. Tarr said the film will be called “Wild Independence,” and is expected to be submitted to Nevada City’s Wild & Scenic Film Festival this year. Grass Valley’s Fable Coffee just did a special roast, calling it Independence Trail blend. According to Tarr, BriarPatch donated $2 for every bag sold.

Canfield said his team is still deciding on the best materials — metal and wood — to use to execute the restoration. State Parks was awarded funding for debris removal and the rebuild. The entire Independence Trail is closed, because cutting it off halfway through would promote noncompliance, Canfield said. Regular patrols ensure that cautionary signage is respected but generally let trespassers off with a warning instead of a legally warranted $250 fine.

Canfield said the State Parks Department and land trust anticipate the project will have the funding to begin on the ground sometime next summer.

Rebecca O’Neil is a staff writer with The Union. She can be reached at [email protected]

To see the complete article and accompanying photos in The Union newspaper, CLICK HERE.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed