Public access to the complete 126-page report CLICK HERE.

The Journal is published with:

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Gavin Newsom, Governor

CALIFORNIA NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY

FISH AND GAME COMMISSION

DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE

CALIFORNIA FISH AND WILDLIFE EDITORIAL STAFF

"Balancing Conservation and Recreation" overview

California is one of the most biodiverse states in the U.S. and while 47% of the state is currently protected, 97% of these protected lands are opened to human access. This report...serves as a starting point for cooperatively exploring the challenge of protecting wildlife while balancing non-consumptive recreation use. If we are to meet conservation goals related to wildlife and wildlife habitat, it may not be appropriate to allow recreation use in all county, state, and federal park and protected areas and at all times.

This study uses years of previous study and new peer-reviewed articles, such a the results of ten years of camera-trap studies on conservation lands, bobcat (Lynx rufus) movement modeling using more than ten years of telemetry data, and compiled 69 journal articles that describe the results of original research examining the effects of non-motorized nature-based recreation on birds.

ALL wildlife are disturbed by mountain biking, hiking, and horseback riding. Biking is the most disruptive, followed by hiking and then by horseback riding, but ALL human activity disrupts wildlife.

Distinguishing facets of mountain biking:

"Together with the extent and creation and use of unauthorized trails and technical trail features by mountain bikers, the mass-marketing of the sport, and the very large numbers of mountain bikers (Burgin and Hardiman 2012), at least four facets of mountain biking distinguish it from other recreational activities such that it may be of potentially greater concern with respect to its effects on wildlife: distance traveled, speed of travel, biking in the dark, and political lobbying and advocacy.

Distance traveled.

-Bikers traveling faster obviously travel farther than hikers per unit time and could therefore disturb more wildlife than hikers per unit time (Taylor and Knight 2003; Burgin and Hardiman 2012); the same applies to bikers and equestrians when bikers travel faster than equestrians. Larson et al. (2016) reasoned that, since motorized activities often cover larger spatial extents than non-motorized activities, it is possible that the effects of motorized activities have been underestimated. For valid comparisons among recreation-related ecological effects, the comparisons must account for distances traveled and the associated levels of disturbance to wildlife along the entire route traveled.

Speed of travel.

-While recreation-related effects on wildlife are generally assumed to be indirect (Dertien et al. 2018), the speed at which mountain bikers travel, combined with their relatively quiet mode of travel, can result in direct disturbance to wildlife. A relatively fast moving, quiet mountain bike may approach an animal undetected until well within the animal’s normal flight response zone. The result may be a severe startle response by the animal with significant consequences to the animal and/or the mountain biker (Quinn and Cherno 2010). The sudden encounter is the most common situation associated with grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribillis) inflicted injury (Quinn and Cherno 2010). Biking-caused wildlife fatalities likely resulting because of bikers’ speed occur with amphibians and reptiles that may be attracted to trails for thermoregulation and are thus exposed to collision with bikes’ wheels (Burgin and Hardiman 2012); photo-documentation provides evidence of three such fatalities in CDFW’s Del Mar Mesa Ecological Reserve in San Diego where a San Diego horned lizard (Phrynosoma coronatum blainvillii, a species of concern under CDFW and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service), three western toads (Anaxyrus boreas), and two Baja California treefrogs (Pseudacris hypochondriaca) were killed by mountain bikes (J. Price, CDFW, personal communication, 2019). The treefrogs appear to have been mating when run over—the photo documentation shows eggs spilling out of the female. Biking is prohibited in this ecological reserve, and two of the run-overs occurred on unauthorized trails (J. Price, CDFW, personal communication, 2019).

Though there are methods (e.g., bells attached to bikes) for mountain bikers to give warning of their approach to other trail users, and these can be effective for this purpose, these methods themselves can introduce additional disturbance to wildlife. And, such warning sounds are ineffective for wildlife whose hearing range does not detect them or who do not hear them soon enough to avoid a collision. Moreover, when recreationists are visible on approach to wildlife, the more threatening (e.g., faster, more direct) the recreationists appear to wildlife (as potential predators), the greater the flight initiation distance from the recreationists (Stankowich 2008). Fleeing from a perceived predator represents potentially needless expenditure of valuable energy.

Biking in the dark.

—Mountain biking in the dark (i.e., night riding), which is on the rise in protected areas, can disrupt the natural balance between diurnal and nocturnal wildlife. Consequently, night riding poses a dual threat to wildlife that exhibit diel shifts toward night: night riding can compound the pressure such wildlife experience from daytime recreational activities by increasing encounters with competitors and even further reducing the time available for foraging and breeding (Reilly et al. 2017). Night riding can also startle naturally nocturnal wildlife and wildlife that has become increasingly nocturnal to avoid daytime recreationists and other anthropogenic disturbances. Generally, temporal shifts by wildlife involve disruptions to both the shifting wildlife and to the wildlife naturally active during the time frame the shifting wildlife move into. In this way, such shifts set both groups of wildlife up for conflict and competition, disrupt predator/prey relationships, reduce feeding/hunting time and success, and disrupt breeding and other activities (Gaynor 2018). Temporal shifts can also result in spatial shifts and thus potentially cause further ecological disruptions. Thus, temporal shifts are disruptive not only to individuals, but also to communities, and ultimately, populations (Gaynor 2018).

Political lobbying and advocacy.

—In part due to the markedly different motivation driving mountain bikers compared to other recreationists in protected areas, especially in the more extreme forms of mountain biking (Burgin and Hardiman 2012), the mountain biking community has come to wield significant lobbying and advocacy pressure throughout the United States. Networking among members if the mountain biking community has resulted in changes in land managers’ decisions (Bergin and Hardiman 2012). In California, a newly formed mountain biking nonprofit aims to gain a voice at the capital with lawmakers to put trail access and trail development front and center (Formosa 2019). And, the community has much experience in planning trail networks, experience that is necessary to negotiate areas appropriate for mountain biking. In San Diego County, the local mountain biking coalition and the United States Forest Service (USFS) work in partnership to build trail networks on national forest lands; because the USFS does not have a budget for recreation, the only way trails will be built on national forest lands within the County is if the coalition pays the USFS for the agency’s sta time, studies and environmental review, and project-processing needed to approve the trail networks (SDMBA 2017). While the USFS-biking coalition partnership may be similar to the accepted practice of an applicant (e.g., utility) paying a lead/permitting agency to dedicate personnel to the applicant’s project(s) or a certain body of work, conflicts of interest are usually inherent in such collaborations. In addition, much of the USFS-biking coalition partnership’s planning process occurs outside of public view, prior to the public knowing anything about it. It is notable that, while not all USFS lands are considered protected areas in the meaning of this paper, the wilderness areas the USFS manages are."

Public access to the complete 126-page report CLICK HERE.

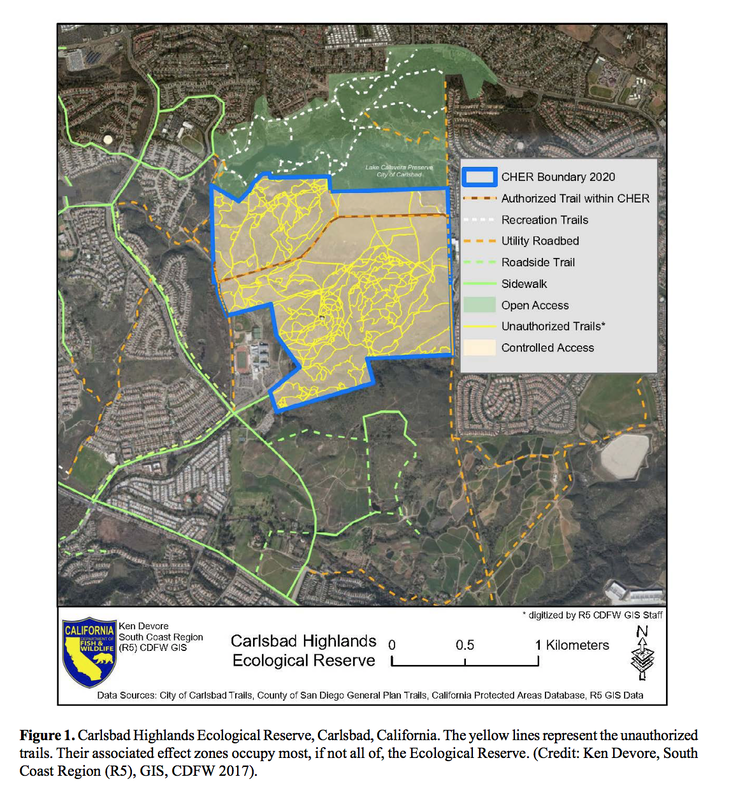

created and maintained by mt. bike riders

RSS Feed

RSS Feed